By Sasha Berkman

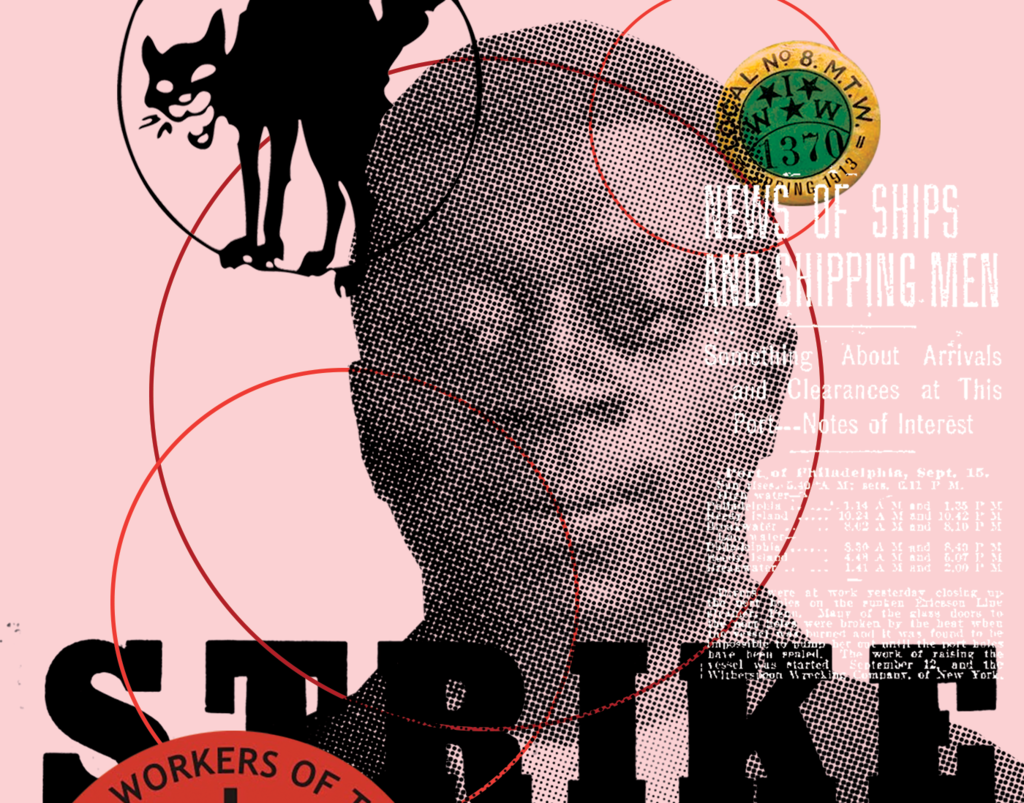

Art by Alex Zahradnik

“Between these two classes [the working class and the employing class] a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organise as a class, take possession of the means of production, abolish the wage system, and live in harmony with the earth.”

-Preamble to the Constitution of the Industrial Workers of the World

In the spring of 1913, the Philadelphia docks were abuzz with activity after 1,600 workers launched a wildcat strike. The spontaneous strike—protesting poor wages and dangerous working conditions—helped usher in a new era of unionism in Philadelphia generally and on the docks especially. According to organizer and local leader Ben Fletcher, the strike allowed the longshoremen to “…[re-enter] the labor movement after an absence of 15 years.”

After many decades of unsuccessful attempts at organizing the waterfront, the controversial Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) met the longshoremen of Philadelphia to finally organize the docks along the Delaware. Ultimately, the strike of 1913 would win the longshoremen a ten hour work day, time and a half for overtime, and union recognition. But most importantly, it began the run of one of the most successful anti-racist and anti-capitalist unions in US history: Local 8 of the IWW.

At the time, Philadelphia was one of the most active ports on either side of the Atlantic, while its longshoremen were among the worst paid in the US. Philadelphia’s business community, politicians, and police department waged a organized and brutal class war against the workers primarily through direct violence, propaganda, but also, importantly, through encouraging racial tensions. According to historian Peter Cole:

[Bosses] sought even greater control over the labor supply by encouraging ethnic and racial divisions among workers…workers labored in segregated groups in most, if not all, of the city’s workplaces.

He goes on to quote longshoremen who refer to the atmosphere at the docks as a “slave market [where employers] play one guy against the other.” Another stated that it was not uncommon for longshoremen to “be pitted against each other, white against black, Irish against the Polish.” Sowing racial and ethnic tensions was an important tool for bosses to more easily exploit their workers. White identity was in part defined by a worker’s wage, against solidarity, and in a commitment to anti-black racism (often taking the form of violent attacks or race riots).

In contrast to the American Federation of Labor (AFL), the IWW embraced interracial unionism, rejected no-strike contracts, and were militantly anti-capitalist. Even the most “progressive” unions at the time kept black workers in segregated unions, often giving them the most difficult and worst paid jobs. This partially explains the prevalence of black and immigrant workers on the docks, as longshoring was extremely dangerous and [sometimes literally] backbreaking work. True to their credo of uniting the workers of the world, the IWW actively encouraged workers of all races to join.

Local 8 would become a “jewel in the crown” of the IWW, as one of its most active and lasting branches. Key to this success, as argued by Cole, was their embrace and active practice of creating an interracial union of blacks, whites, and the many ethnic groups working the docks: “Local 8’s power came from its commitment to solidarity, especially racial and ethnic equality, which always proved a challenge to maintain.” Their success was also due in part to the tireless leadership of organizer and orator Ben Fletcher.

Born in Philadelphia in 1890, Ben Fletcher became one of the key figures in organizing Local 8 of the IWW, rising to a leadership position by his early twenties. In 1913, he became the secretary of the IWW District Council in Philadelphia, and in that role, he helped lead Local 8 and the longshoremen of Philadelphia through many successful strikes winning bold demands for better pay and more humane working conditions. They helped lead solidarity strikes with teamsters and sugar workers, and at their height began organized other trades such as sailors. According to Cole, “refusing to sign contracts, acting at the point of production, extending their power along the waterfront, trying to bring all maritime workers into the One Big Union – the longshoremen of Local 8 were squarely within the era’s wave of new unionism.”

His success, and the threat he posed to the business class, may be best evidenced in his arrest along with other IWW leaders for the crime of organizing workers during wartime: of the 100 IWW leaders arrested and convicted, Fletcher was the only black man. Amusingly, as the presiding judge was giving a statement mid-trial, Fletcher, in an aside to IWW General Secretary-Treasurer “Big Bill” Haywood, remarked that the judge used “poor English” and “long sentences.” A master orator to the end.

Fletcher would ultimately serve three years of a commuted ten year sentence. Local 8’s strength declined in those years due to attacks from the state and employers, as well as internal turmoil. Fletcher would remain a member until his death in Brooklyn in 1949. At his funeral, fellow worker and Wobbly* Sam Dolgoff spoke: “Ben, we won’t forget the great part you played in the struggle to emancipate the workers and we will carry on inspired by your example.”

This period in Philadelphia’s history is perhaps one of the truest realizations of the ideals of socialists and anarchists. The impacts of organized labor, many that the IWW championed, are everywhere: in the eight hour day, in union contracts, in the realization of the weekend, etc. While these victories may erode, the heroic struggles and importance of solidarity shine through nonetheless. And crucially, this era teaches us lessons of how race became a central pillar in structuring the economic and social order of the United States, an important lesson for genuine anti-racist organizing.

*informal term for a member of the IWW

Sources

Wobblies on the Waterfront, Peter Cole (book)

No Jobs on the Waterfront: Labor, Race, and the End of the Industrial City, Peter Cole

Ben Fletcher 1890-1949, LibCom.org

Ben Fletcher: Portrait of a Black Syndicalist, Jeff Stein

. . .

If you enjoyed this post, help us grow by contributing to the Philadelphia Partisan on Patreon.